By JIM ENGSTER | President, Tiger Rag Magazine

Imagine if today, LSU football featured a pair of superstar running backs who finished 1st, 2nd, and 3rd in Heisman voting in a span of five seasons.

If LSU suddenly showcased back-to-back marquee stars in college football and lost four games in four years in the junior and senior campaigns of those players and finished 1, 3, 3 and 4 in national polls in those years, the eyes of the nation would be focused on Death Valley, and LSU football would dominate twitter exchanges and the 24-hour cable sports cycle.

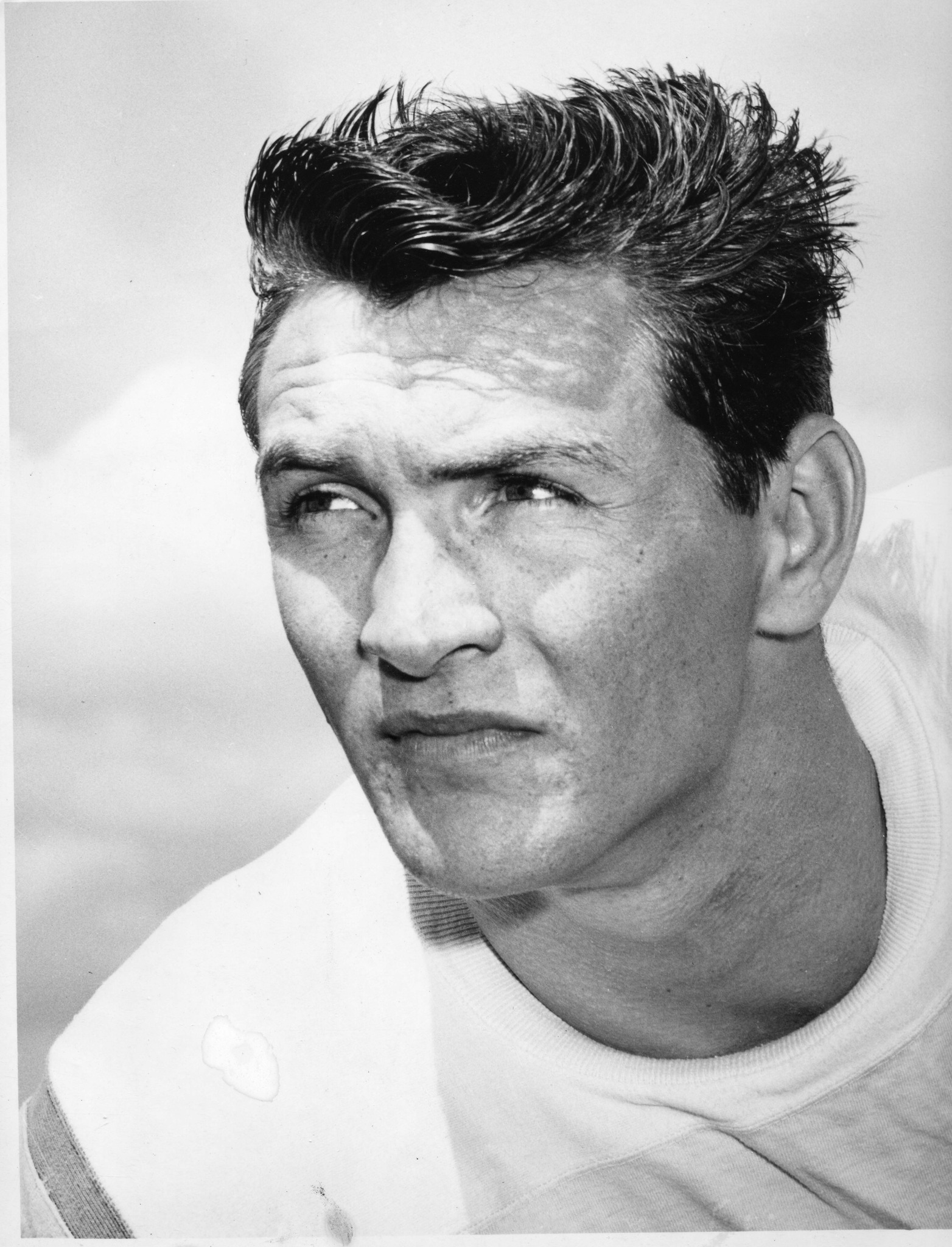

LSU produced its two highest Heisman balloters between 1958 and 1962 with Billy Cannon winning the award in 1959 after finishing third in the voting of 1958, and Jerry Stovall finishing second to Oregon State’s Terry Baker in 1962 in the closest balloting to date at that time.

Cannon was the first player selected in the NFL and AFL Drafts of 1960 and Stovall went second in The NFL Draft with Baker the top player chosen in 1963.

The LSU record in the junior and senior years of Cannon was 20-2. Stovall led the Tigers to a 19-2-1 mark in his final two seasons as a Tiger. In the year between, LSU struggled to a 5-4-1 mark in 1960.

Both men had distinguished NFL careers, lost favor with their alma mater in their 40s, but have since been embraced enthusiastically at LSU as senior citizens.

Cannon’s past includes a stay in a federal penitentiary on a counterfeiting caper in 1983; Stovall was dumped as LSU head coach the same year in perhaps the most public firing spectacle in the history of the college game.

Cannon has served as the prison dentist at Angola for a couple of decades while Stovall capped his athletic odyssey by heading the Baton Rouge Sports Foundation for more than 20 years.

It is curious that both men chose to spend their golden years in the place where they achieved their greatest glory as well as the location that brought them their most humiliating pain and shame.

Cannon is 80, more than 60 years removed from his freshman year at LSU. Stovall is 76 and 55 years past his exit as an exquisite standout on the first team for Charles McClendon as LSU’s head coach. The first lines of the Cannon and Stovall obits will include their LSU heroics, and they loom large in any room where Tiger fans gather.

When No. 20 was leading LSU to the national title in ’58, No. 21 was a senior at West Monroe High School. A year later, Cannon captured the Heisman and starred in the most famous play in LSU’s storied history, the 89-yard punt return to beat Ole Miss on Halloween night of 1959.

Stovall was a freshman and not eligible for varsity completion, but he inherited the role of LSU’s best player after Cannon joined the Houston Oilers.

Cannon led the AFL in rushing in 1961 and helped the Oilers to their second consecutive AFL Championship. Cannon scored the only touchdown against the San Diego Chargers in a 10-3 victory in the title game. A year earlier, Billy as a rookie went 88 yards for a touchdown on a pass from George Blanda as Houston beat the Chargers 24-16 in the first AFL Championship Game.

Cannon’s best days in professional football came later as a tight end with the Oakland Raiders of Al Davis. The Raiders won the 1967 AFL Championship, then lost Super Bowl II to Green Bay, 33-14.

Stovall was a three-time Pro Bowl selection in his nine years with the St. Louis Cardinals and is one of the last players in the league to negotiate his own contract.

Both men have avoided cognitive deficits that have plagued so many players of their generation. Cannon and Stovall remain lucid and lively with several lifetimes of anecdotes at their disposal.

Saturday before the LSU-Texas A&M game, Cannon and Stovall will appear at the Lod Cook Hotel at 10 a.m. to be interviewed by the fellow writing this column. The event is free and open to the public.

Final Olympic quest for Lolo Jones?

The most famous worldwide athlete from LSU since Shaquille O’Neal is Lolo Susan Jones.

At 35, Lolo is a decade younger than Shaq and is still very much part of the sporting scene. She is the most charismatic athletic icon from LSU since Pete Maravich was captivating the masses on the court in his prime.

Jones is valiantly striving to be a member of the U.S. Olympic bobsled team at the 2018 Winter Games in South Korea. It is likely the last shot for Lolo to collect an Olympic medal.

The Des Moines, Iowa, native was steps away from a gold medal at the 2008 Summer Games in Beijing when her right foot clipped the next to last hurdle in the 100 meter event. She narrowly missed capturing a bronze medal in London in 2012, finishing one-tenth of a second out of third place.

Jones competed as a bobsled Olympian in 2014 in Sochi, but did not come close to the winner’s circle in that endeavor.

She now competes as a brake woman on the mixed team and won a gold medal in the mixed team competition at the 2013 World Championships. Despite her versatility and tenacity, Lolo creates a buzz when revealing other aspects of her life.

An Associated Press account of the latest athletic foray for Jones goes this way.

“Her level of fame has created some jealousy among other athletes over the years, in both bobsled and track. Her tweets and generally outspoken ways have been known to rub people the wrong way. Her beliefs — she’s a Christian who reads her Bible daily and is still waiting to have sex until marriage — have been a lightning rod for critics.”

Jones has added 20 pounds to pursue the bobsled dream and has won seven medals in 16 World Cup events in this sport. And she plans to return to the track next year with a return to her leaner hurdling frame.

Jones is a millionaire and has been featured on Dancing with the Stars and in the Body Issue of ESPN’s magazine. She has grown accustomed to receiving mega-star attention without the Olympic medal to show for it.

“There’s so much frustration and so much pain,” Jones said in a tearful interview with the A.P. “I try not to be jealous of other people I’ve beaten along the way who have gone on to get medals. What have I done wrong? Why can’t I finish this? And then I get teased for it. It’s very frustrating.”

Joe Namath never won another playoff game after winning Super Bowl III with the New York Jets when he was 25. But he remained the NFL’s most charming and mysterious figure for another decade as he continued to play through extraordinary pain with braces attached to his gimpy knees.

Like Namath, Lolo is making a case that an exceptional competitor accompanies the film star face and magnificent physical presence. Whatever the outcome of her current pursuit, she has exhibited ample courage by seeking excellence on her own terms.

1 Trackback / Pingback