Thirty-two years after he became and remains the only LSU player ever to be chosen No. 1 overall in the Major League Baseball draft, Denham Springs native Ben McDonald is a family man living life in his hometown on his own terms, mixing a busy baseball broadcasting career with his love of the outdoors while keeping track of his son Jace, a pitcher and student body president at LSU-Eunice. After a high school career as a three-sport athlete, McDonald arrived at LSU in the fall of 1986 and played both basketball and baseball for a season before concentrating on baseball as a sophomore in 1988. In two seasons, he filled the LSU record book with his name, including striking out 202 batters (still an SEC record) in 1989, the same season he became the first and only Tiger ever to win the Golden Spikes Award as the college baseball’s best player.

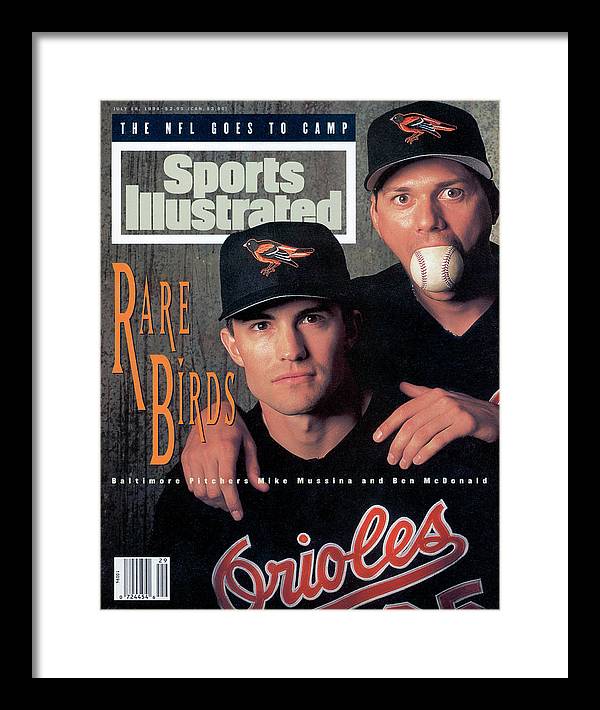

In nine MLB seasons before he retired at age 29 from injuries, McDonald was 78-70 with Baltimore (seven years) and Milwaukee (two years). He was the first LSU baseball player to have his jersey retired and is a member of the College Baseball and Louisiana Sports Halls of Fame.

Tiger Rag assistant editor Will Weathers chatted with the 53-year old McDonald in mid-January as he was driving to his camp in Mississippi.

TIGER RAG: Did you ever regret trying to initially play baseball and basketball at LSU rather than just play baseball? Why play both and when did you ultimately decide it was too much?

BEN McDONALD: I don’t regret any of that. If I have any regrets at all it’s probably not going out and punting for the LSU football team when they asked me to punt my freshman year. I had punted really good in high school and led the state in punting my freshman year. They asked me to come and punt for the football team, but I couldn’t do it because I was already playing basketball and baseball and I wasn’t an especially strong student to begin with. It was all I could do to stay eligible playing basketball and baseball.

I don’t regret playing basketball. That was my love growing up and it really was my favorite sport growing up. I was more highly recruited coming out of high school to play basketball than I was baseball. I was just starting to come into my own in baseball, but I loved basketball. I loved my days with Dale Brown and those two years I spent with him. Getting to go to an Elite Eight in the NCAA tournament, making a deep tournament run. All of those things are memories that will last forever with me.

The only reason I gave up basketball is because my fastball ticked up when I got to LSU and it really ticked up at the end of my freshman year and when I went to the summer league in Alaska and got up to 97 miles an hour. At that point, I kind of knew baseball was probably going to be my future if I made it to the next level. Because we made that deep run in the NCAA tournament in basketball, I didn’t get out for my freshman year in baseball until the NCAA tournament was over. I missed all of the preseason. They were playing SEC games by the time I got out there and I knew that set me back in baseball and of course I knew the next summer was the Olympic summer. Coach Bertman talked to me and said he wasn’t trying to put any pressure on me but he saw how I was progressing and if I had a good sophomore season, I could wear the red, white and blue in the summer, pitch in Seoul, South Korea and have a chance to win a gold medal. I knew something like that didn’t come along very often.

At that point, I told Coach Brown I was giving up basketball and he was disappointed. He always told me I could have played in the NBA, but whether I would have been as successful as I was in major league baseball, he couldn’t answer that. It was heartbreaking for me to tell him that. He called me up in October or November of that year when I was a sophomore and told me the whole team had come down with mono and they didn’t have enough players to practice. I told him I was on my way. I went back to basketball, gave them another body to practice against and got to play a little bit. I told Coach Brown that when January 1st rolled around, I had to get to baseball. I got my legs in such great shape playing basketball, going up and down the court and getting my wind. I tell a lot of young people the reason why I could start a game off, and the first pitch be 95 and after 140 pitches, I could throw the 141st pitch 95 miles an hour, was because I had my legs and my wind in such good shape from playing basketball. I didn’t mind it. When January 1st rolled out, I checked out and as they say, the rest is history.

TR: Describe the difference in approach and temperament of playing for Dale Brown and Skip Bertman?

BM: Both guys are amazing coaches. Both guys know how to get the best out of their players. To me, that’s the mark of a great coach. Everybody’s buttons can be pushed different ways and for a coach, what you do for one kid you may have to do something totally different for another kid. Coach Brown knew how to do that, and Coach Bertman was a master at it, too. There were a lot of similarities between the two. They were big time motivators, guys that just made you feel good. It was tough love. One day we’re going to tear you down and then they’re going to build you back up. When you’re 18 to 21 years old, you don’t always understand what coaches are doing to you. As I got older and had kids of my own, I understood them. I found them to be very similar in a lot of ways of wanting to play for a guy, loving a guy and knowing that he cared about you as much as a ball player than he did you as a person on and off the field. To this day, I still get emails from Coach Brown, stay in touch with Coach Bertman. They still really care about you.

TR: How much do you feel like you helped to lay a foundation for LSU’s success after the year you won the Golden Spikes Award in ’89?

BM: We take pride in it. Even Coach Bertman calls 1989 his sixth national championship. There was the story with Texas A&M and how they were supposed to win everything, yet we went in there and beat the best team in the country and went to Omaha. You talk to Coach Bertman, he said we were the stepping stones for what would come later. Coach Bertman would always say you’ve got to be there before you can win it. The truth of the matter in ’87 we were just happy to be there. Then the ’89 team, I felt we really had a chance to win that first national title. I felt like we were that good and then we got stuck at A&M in the regional and didn’t know if we could come out of that. By then, I was out of gas because I had thrown so much, and I didn’t have a whole left in the tank. I wasn’t at my best in Omaha and we got beat.

Then, the ’91 team comes along and says, ‘Look, LSU’s been to Omaha three different times. They know what it’s about, now it’s time to go win it.’ Coach used to say the first one was the hardest one and sure enough when they won it in ’91 we all know what happened after that. The national championships came in bunches. We kind of paved the way of building the LSU program which was something we took a lot of pride in. All the credit goes to Coach Bertman. He had a vision when he came to LSU which was a below average program and what it could be with some work and boy did he ever build it. He built it into what it is today.

TR: You were the top pick overall in the 1989 MLB Draft but had your career curtailed after nine years by injuries. What’s your biggest takeaway from your time in professional baseball?

BM: I’m thankful I got the opportunity to do the things that I got to do. Very few players have their careers end the way they want to. Very few get to walk off the field at their own doing. The Cal Ripkens, Kirby Pucketts, Paul Molitors and Derek Jeters, those are guys that are few and far between. Most guys get told it’s over and that’s just the reality of it. That happens. For me, it was injuries. I didn’t have a choice. I wasn’t one of those guys laboring around, trying to hang on and past his prime. I hate to see those kinds of guys. Although they’re still competitive in what they do, they’re just not what they used to be. I often hoped that I would have that choice one day to know it’s time to ride off into the sunset.

I was 29 years old and had nine years in the big leagues and felt like I had just started to figure it out. When it happened, I felt like my best years were in front of me. I’ll be the first to say that my career didn’t go the way I wanted it to go because of injuries. The good news for me is when I talk to kids, I tell them to suck out as much of the game as you can every day because you never know when it’s gone. When I lay my head on my pillow at night, I don’t have any regrets about my career. I always tell young kids that regrets are the worst things in the world. You don’t want to look back on your career after five years or 10 years from now and say, ‘Why did I quit the college team. Why did I quit in high school? How good could I have been? Why didn’t I take a chance and go do that’?

I don’t have any of those things because I know I worked as hard as any human being worked to be the best that I could be. I enjoyed every bit of being a big leaguer. When I started, I felt I could play the game for 15 years. I feel like I had the body type, I felt like I had the stuff and the mentality to go do it. While my first years in the big leagues were hit and miss, I had some great games, and I had some bad games. I didn’t have the luxury of learning how to pitch in the minor league system in front of 600 people. I was 21 years old in the big leagues learning how to pitch in front of 40-50,000 people every night. I went home plenty of nights and banged my head on a wall and cried wondering why I couldn’t have success at the big-league level, but it never deterred me from trying to be the best that I could be. I just kept plugging along and moving forward until the light bulb started to flicker a little bit and eventually it did after a while. I don’t have any regrets about my career. I wish I wouldn’t have gotten hurt. I wish I would have played 15-16 years, but those are things people wish for. At the end of the day, I’m just thankful for having the opportunity to get to play nine years.

TR: Given the fact that you never took any broadcasting classes while at LSU, are you surprised at the trajectory your career has taken?

BM: I really never set out to do it. I never graduated from LSU. I got selected my junior year and was the first pick, so I took off because I didn’t think I could do any better than that. The Olympic year before that, we got back at the end of October into my sophomore year that fall semester, the NCAA granted a handful of us a waiver and we didn’t have to go to school that fall semester. I really got in only five semesters while I was there.

I was just getting into broadcast journalism, that part of the major and started taking some speech classes. Pro ball took front and center and then I was out of pro ball. If it wasn’t for Skip Bertman, I wouldn’t be in broadcasting. He came to me one day and thought I’d be really good doing ball games. I told him I hadn’t studied that or knew much about the industry at all. He called the folks at CST and got my foot in the door and that’s how it all began. I did three years of that and then ESPN needed a guy to do a super regional in Baton Rouge one year.

At that point, I realized I wasn’t prepared. I wasn’t even keeping score, I didn’t have notes, I didn’t have a scorepad. All of a sudden, I realized that if I was going to do this, and talk about pitching, I had to know more. You have to know where kids are from and what they did last year and where the coach is from. You’ve got to know a lot more about it. I buckled down and said `If this is what it’s going to be and maybe I’ve got a chance of making a little bit of money if I improve myself.’ I dove a little deeper into it and got a little bit better. The more you do it the better you get at it. You start to figure it out.

I guess ESPN liked what I did at the time. They started inviting me to do the SEC tournament and a regional here and there and some stuff along the way. About six years ago, I took the big jump with the SEC Network. I got invited to go to Omaha and started doing that about four years ago. It’s gotten bigger as we’ve gone and through that process, I think the Orioles saw that I was doing a pretty good job and liked what I did. They started inviting me back about eight years ago, doing 15 to 20 games on radio and TV and that’s grown where I’ve got more games with the Orioles. I cut back my ESPN events to do more Orioles stuff.

I love the college game. It’s probably still my most favorite to do. Before COVID hit, the major league life was a lot better.

When you’re doing college games, we very seldom broadcast an entire three-game weekend series. We’re basically doing one game out of the three to get as many series as possible on TV. It can be a challenge. There’ve been times when I’ve flown into Nashville on a Thursday for Vanderbilt and Florida, hopped an airplane Friday morning and go to do LSU at Georgia on Saturday night, hop an airplane Sunday morning and fly into wherever and do another game.

The major league game is a little bit different. You travel with the club and if you’re on the road, you’re there for three or four days. If you have a homestand in Baltimore, you may be there for 10 to 12 days. That attracted me to the major league side a little bit more and that’s why I took on more work with the Orioles and signed a three-year contract.

I signed a three-year contract last year with ESPN as well. I’m still going to do the major (college) events, so I get 10 to 12 regular season games but I’m still on the SEC tournament, regionals, super regionals and the College World Series.

TR: You’re one of the few college baseball announcers that’s universally liked, even throughout the SEC where fans can hold an announcer’s alma mater against them. Why do you think that is?

BM: I had a little bit of that at first, especially from the A&M fans for the obvious reasons. Some people aren’t ever going to forget, and I get that. I really went out of my way to make sure that I was neutral. I felt like if I wasn’t neutral on anything I did, then I’d lose my credibility. What was even more important than that was that I told the truth. That’s what I try to do.

If LSU stunk that night, I’m going to say LSU stunk that night. If I feel like Paul Mainieri made a wrong move that night, I’m going to speak my mind and say I didn’t like that decision. I do the same thing for Mississippi State and for my good friend Mike Bianco at Ole Miss. He was my catcher at LSU, and I’ll do the same thing for him. I think my credibility and why people like me is because I get on there and tell the truth. I say what I see on the field and then I try and not hold anything back.

I’ve never run-down kids in college or the professional level. I try to be as honest as I can. Because of my honesty, and I know some people get upset, but my job is to go out there and call the game and what I see, but I do it in a way where I’m not running anybody down. That’s never my intention.

TR: What was it like as an announcer with the Baltimore Orioles without fans at major league games last season?

BM: That was a challenge. As an announcer, or a ballplayer, you feed off crowds. Whether it’s the home or visiting crowd, you feed off that. There’s just something about it that gets the juices flowing a little bit. In talking to the players at the big-league level, it was a challenge for them because you didn’t have that 35,000 in the ballpark. They had to create ways to be energized. They figured it out along the way, found a way to go about doing it and I think some handled it better than others. For the rookie coming up, it was a blessing for some players. They didn’t have to deal with a rowdy 35,000 fans in Yankees Stadium. For some of the older veteran players, they feed off the energy level.

For announcers, it’s kind of similar for us. Whether we’re at home or on the road you feed off the crowd, the atmosphere and the energy the crowd brings. It was an unusual process for us because we didn’t have that. You had to make sure you were showing the same enthusiasm as an announcer would in a normal situation. In Baltimore, we could watch the field and could see what was going on. That made it easier to call a game. When they went on the road to play, we didn’t travel with the club like we always do. We actually called the game from the press box in Baltimore, but we were watching it on a big screen TV like you were sitting in your living room calling a game.

That was even more of a challenge because you couldn’t see everything going on at the ballpark. You couldn’t see if there was a runner at second base and if there was a base hit to right field, you couldn’t tell if the runner got a good jump or not was the reason he made it home or got tagged out at the plate. Some of the camera angles you couldn’t tell when the ball got down in the corners, you didn’t know if the outfielder bobbled it or not. Little things like that were a big challenge for us to do those games.

It was a unique year and difficult in a lot of ways. When I went to Baltimore, they didn’t want me flying back and forth for the obvious reasons of not getting COVID or having a higher risk of contracting the virus. I actually had to stay in Baltimore for 2 ½ months and never got to come home. I stayed by myself in a hotel room and that was a difficult time, just being away from the family. My dad got COVID during that time. I couldn’t go home and see him, and I couldn’t have seen him anyway if I was at home because they weren’t allowing anybody in the hospital. That was a challenge for me. It was just a weird year all around.

I always said going through that process that we were playing baseball again was a good thing. Major league baseball showed as a major sports league that you could compete, that you could do this thing even in the middle of a pandemic. I’m thankful that major league baseball had the guts to go out and do it and wanted to do it. It was only a 60-game schedule, which I felt it could have gotten done faster. I think they could have played 100 games. But you’ll take 60 over nothing and of course the playoffs and the World Series were a hit.

TR: Your broadcasting schedule has increased in recent years as your career has taken off from doing just college games. What’s your preliminary schedule for 2021 look like?

BM: All of LSU’s games are on a digital network and you’re able to watch those on your phone. Before the pandemic in 2019, I did 134 games counting everything. Last year I was scheduled to do 129 games before the college season got cancelled. This year I’m scheduled to do 82 games with the Orioles and 40-something with college, so it will be in the 120-something range. Then you add the digital stuff in for another six or eight. It will be close to 130 games assuming everything goes off as planned.

TR: Last year you were asked for the first time by the Orioles to go to spring training and serve as an instructor in uniform for two weeks. What was that experience like?

BM: I really enjoyed it. It was an honor when they asked me. It just blew my mind when I walked out there and there were five pitchers throwing in the bullpen to five catchers. Behind each pitcher was a guy on a computer and all of these machines that detect spin rates and grips, and every pitch that a pitcher threw went into a computer. After each bullpen session, they sat down and went over grips and what spun the ball better.

It was really cool for me because I got to catch up on all the new analytics that’s out there and the way they do bullpen stuff now. It also gave me time to get to know each pitcher for the Orioles and what he likes to do and what are his favorite pitches. It was valuable information. I was able to help teach and give my input on some of the kids if they asked. I call them kids, but they’re men that are still kids to me in a lot of ways. The Orioles are still a very young team. There are a lot of young guys still feeling their way through the big leagues for the first time. They have a lot of questions from the time I pitched and what we did to train our bodies and how we set up hitters. It was fun to sit back and share information and listen to them and see what they were thinking along the way.

TR: Is it easier to be a college pitcher now than say 15 to 20 years ago when the equipment (livelier baseballs) favored the hitters?

BM: It was a tough time to pitch in the pre-BBCOR bats era about seven or years ago. When they put the BBCOR bat in, then it became real pitcher heavy. It seemed like everyone had a starting pitcher with an ERA of 1.00. They swung it too far toward the pitcher at that point. Then about four years ago, they implemented the new baseball which is more of a minor league baseball and basically has the same exit velocity. It has more carry to it, the ball flies farther. It’s as fair as it’s been in college baseball as I can remember.

In my time at LSU, the ball flew out of the ballpark. Anybody could hit a home run, you had the “Gorilla Ball” stuff come along. Then, they got too far with it and pitchers just dominated the game and quite frankly the game became boring. I remember going to Omaha and there were three home runs hit the entire time. That was just ridiculous. People got bored with it. There were 3-1, 2-1 games and people don’t mind those kinds of games every now and then, but it can’t be every game. Then, they changed the baseball and now I feel like the game is at its most fair point. If you’re a big, strong guy and a pitcher makes a mistake and you barrel the ball up, it goes over the fence. That’s the way it’s supposed to be.

You can look at the numbers in pro baseball and there’s no doubt the balls are amped up. Balls are flying out of the park, but people want to see the ball leave the park. More runs scored is what most people like.

TR: If you were named commissioner of college baseball, what would you do to improve the sport?

BM: One of the big things they’ve tried to get passed for a long time is adding another paid assistant coach. I get the money side of it, but when you look at baseball and the number of players they have on the roster vs. how many full-time coaches they have, it’s the worst in all of college sports. I would love to see another full-time assistant.

I would love to see the 11.7 (scholarship limit) go away. That’s another sticking point for me. You take 11.7 divided amongst a roster, which has changed this year because of COVID, but I would like to see more scholarships at the D1 level. Maybe go to 14.

I think college baseball’s in a great place and continues to grow from a national standpoint. I think they’ve done a wonderful job of getting it out there with the SEC Network, the ACC Network and Pac-12 Network. ESPN and ESPNU are carrying more games. The digital thing is huge because you can pretty much follow for your favorite college team on your phone or iPad even when they’re not on regular TV. All of those things have helped grow the game.

TR: Give me your best tailgate foods from around the SEC, not including LSU. Name the items and what school’s fans usually share some with you?

BM: You start at Mississippi State. That place is like no other, especially with the new ballpark. The Left Field Lounge was known nationwide, even back in the late 80s when I was playing. Those fans were and still are some of the best in all of college baseball. They will scream at you, cuss you, raise hell, talk about your momma and all of those things during the game. But in between games of a doubleheader, they would bring you whatever you wanted like barbeque ribs. It was always a great place to play because of the environment and the way the fans treated you. It’s still that way. They still feed me. They invite me out to the Left Field Lounge, go out and have some barbeque ribs and drink a beer with half of them and have a good time. In the SEC, it’s hard to beat Mississippi State.

Ole Miss is a lot that same way, too. They do a lot of stuff in the outfield as well. There’s a lot of cooking going on out there. It’s the kind of group you’re going to hang out with after a game. Between LSU, Mississippi State and Ole Miss, they’re above and beyond most everybody else as college baseball atmospheres and everything that goes into it, .

Vanderbilt, Florida and Georgia do a little bit of it. Their fans are into it, but not as big on tailgating as the other schools are.

Be the first to comment